The sculpture park is a particular type of place, a particular type of arts institution. A phenomena unique to the medium of sculpture, save perhaps for a select sort of architecture, the sculpture park is traditionally set within a bucolic, natural landscape or, on a smaller scale, framed as landscape, open air museum annex. It provides a unique if unavoidably artificial manner in which to view sculpture – out of doors, subject to the elements, and transformed (or dwarfed depending on the scale of the work) by the expanse of its surroundings. This tension–between seeing sculpture situated in such a setting and knowing it is a foreign object within that environment–is one of the things I find more intriguing about this type of venue. The awareness of institutional context never really goes away, but if done really well the sculpture park can produce transformative moments when a piece of sculpture looks like it was always meant to be there, its form so radically altered by its situation; or in reverse, the landscape takes on a completely different character when seen through or around an object.

A perfect example of the sculpture park done right can be experienced at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Located near Wakefield, about 2o miles south of Leeds in the north of England, YSP occupies the 500 acres of the Breton Hall Estate, which was built in 1720. Temporary exhibitions fill the beautiful and varied indoor galleries. The Yinka Shonibare’s Fabric-ation is currently on and is spread across a number of these structures, including the main Centre, the Underground Gallery, and the beautiful St. Bartholomew’s Chapel which is hosting a video piece (And as a small aside for those who are equally enamored with this last venue, please consider donating to the YSP Chapel restoration project). There is a lovely cafe on the premises, which overlooks the rolling hills of the surrounding countryside, and walking around the expansive grounds, filled with distractingly charismatic sheep, dogs playing, people picknicking, and of course world-class modern and contemporary sculpture makes for a stellar afternoon.

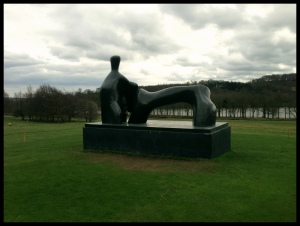

None of this is that revelatory to anyone who has visited, and my intent here was not to write a (genuinely) glowing review of the place, but I suppose it needed to be said all the same, if only to add to the choir singing YSP’s praises. Getting back to my initial observations on sculpture parks, however, I want to also be a bit more (sculpture) specific as to what struck me during my afternoon. Upon arriving at the Park, numerous bronze Henry Moore’s are visible. It is not a surprise that the YSP would have so many Moore’s and Barbara Hepworth sculptures, considering both were born in Yorkshire, but seeing these works in this landscape was a bit of a revelation. I definitely encounter a lot of Moore-detractors or at least those who have little interest in his work, but pieces like Reclining Figure just make sense there; the almost seem to emerge from the earth standing as both modern testaments to abstraction and monuments to the particular place in which they sit.

Walking around this section of the grounds, I also became intrigued by two empty, deteriorating plinths – and yes, in the midst of some many proper sculptures, the fact I spent a lot of time looking and thinking blocks of concrete has an element of ridiculous to it. I loved though how approaching these things, I first questioned if they were sculptural objects. I walked around and looked in, wondering if it was minimalist cube from the 1960s or an ironic quotation of that moment by some hot, young artist – the institutional context clearly exerting its power. Then, realizing these things were functional objects waiting to support a piece of sculpture or even their own destruction, I enjoyed their presence even more.

Walking around this section of the grounds, I also became intrigued by two empty, deteriorating plinths – and yes, in the midst of some many proper sculptures, the fact I spent a lot of time looking and thinking blocks of concrete has an element of ridiculous to it. I loved though how approaching these things, I first questioned if they were sculptural objects. I walked around and looked in, wondering if it was minimalist cube from the 1960s or an ironic quotation of that moment by some hot, young artist – the institutional context clearly exerting its power. Then, realizing these things were functional objects waiting to support a piece of sculpture or even their own destruction, I enjoyed their presence even more.

So often in museums, whether indoors or outdoors, we are presented with immaculate, highly calculated displays that attempt to mask the apparati of art. These plinths, however, were ragged, their exteriors crumbling and their purpose denied. Yet their presence made me consider the temporality of both neighboring sculptures and the physical place in which I stood. Moore’s bronze figures indeed express the gravitas of permanence but landscapes change, plinths crumble, and no work of art is guaranteed to last forever. These concrete slabs and structures serve as poignant examples of humanity’s sisyphean attempt to control both the passage of time and the form of our environment.

So often in museums, whether indoors or outdoors, we are presented with immaculate, highly calculated displays that attempt to mask the apparati of art. These plinths, however, were ragged, their exteriors crumbling and their purpose denied. Yet their presence made me consider the temporality of both neighboring sculptures and the physical place in which I stood. Moore’s bronze figures indeed express the gravitas of permanence but landscapes change, plinths crumble, and no work of art is guaranteed to last forever. These concrete slabs and structures serve as poignant examples of humanity’s sisyphean attempt to control both the passage of time and the form of our environment.